- Home

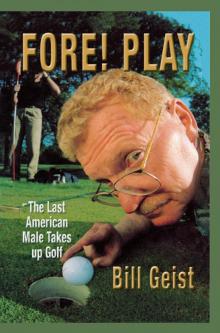

- Bill Giest

Fore! Play Page 2

Fore! Play Read online

Page 2

I can’t argue with any of that. I’ve had terrific times out on golf courses on beautiful days with partners who could hit bad shots and laugh about them. It’s just the damned frustrating, maddening, impossible, merciless game I hate.

But I want to see my friends and about the only place to do that anymore is on a golf course.

So, I’m giving it a try. But I’m not going to call it a “try,” I’m calling it “one man’s personal journey” so maybe I can attract a little interest from Oprah’s Book Club. I approach this with some hesitation, steeling myself for humiliation, and fearing addiction.

I mean these golf nuts are gone, folks. Round the bend. And they’re not coming back. I have friends who are plopping down $1,500 or more for clubs, $50,000 to join the country club, taking golf vacations to California and Scotland, and moving to golf communities so they can literally live on the golf course (and have my golf balls land on their coffee tables). There are coffins decorated in golf motifs.

Now, if golf were a religious cult, and I certainly don’t mean to imply it isn’t, and you saw your friends suddenly acting in such an irrational fashion, you’d have them deprogrammed!

And if someone like Chi Chi Rodriguez should take them on a golf vacation to Guyana and tell them they are all going to a better place, the big country club in the sky, where there are no monthly food minimums and they will play par golf with custom Callaway clubs on a Robert Trent Jones–designed course every day for all of eternity … what do you think happens?

They drink the Kool-Aid, no question.

1

A Life in the Rough

I am from a golf-deprived background. No one taught me to play. I picked up the game in the 1950s on the hardscrabble streets of my hometown, Champaign, Illinois, first in my own yard where my brother Dave sank a number of tin cans, then at a miniature golf course across from a trailer park, and finally at a little 9-hole public course between a cemetery and a pigpen.

Of the two forms of golf, little and big, I preferred the mini version, where there was always a lot of laughing, and where a really bad shot—one that hit another golfer or another golfer’s Buick, or one that skittered across the street and had to be played out of the Illini Pest Control parking lot—was always considered the very best shot of the day. It takes a certain skill to get some loft on the ball and drive it that far with a putter.

We played (for 35 cents, as I recall) on warm summer nights, the course semilit by dim bulbs strung here and there, accompanied by the sounds of crickets and top ten tunes like “Green Door” or “Tammy” that were trying to make themselves heard on the single raspy speaker attached to the shack. The balls were colorful and the clubs almost dangerously barbed and ratty, having the look and feel of spoons that had been dropped into a garbage disposal—except those weren’t invented yet. There were always friends there, and sometimes a group of cute girls in short shorts that would cause my friends and me to show off—sometimes in ways that involved minor property damage and expulsion.

It was exotic. There was the little bowed bridge over a six-by-eight-foot pond—probably the largest body of water in the county. And there was the windmill. How clever. Turns out all mini-golf courses have windmills, but I didn’t know that. We didn’t get around much. Provincial? Our high school foreign exchange student was from America. Hawaii. Who knew?

Mini-golf was fun. But big golf is not played for fun per se. You don’t hear a lot of laughing on your standard-sized courses. Oh, there was some laughing at that public 9-hole course, where players were generally awful, not serious about the game, sometimes drunk, sometimes without any golfing equipment, and occasionally there just to make out. You never see couples making out on the country club course or at those golf tournaments on TV. Too bad.

My friends and I didn’t know how to play, and we didn’t know that the 9-hole course was as bad as we were. A round of golf cost next to nothing and that seemed a fair price. Actually, I’m not sure we paid. I think if you started on the second tee you didn’t have to pay.

The course had no landscaping as such: no trees, no berms, no sand traps, no rough—-just the tees, straight fairways, and flat little greens. Like a sod farm. On one fairway, the designer decided to get a little tricky, placing across its width a foot-high, grass-covered hurdle that resembled an enlarged speed bump—although in retrospect that might have been a sewer pipe or the work of a large rodent.

That was all to the good. We were not accustomed to trees—all of which had been wiped out by Dutch elm disease—or topographical aberrations like slopes, knolls, or knobs—let alone hills. We were flatlanders. The land was flat in every direction for hundreds of miles. My driveway was the steepest slope in town. The first time I saw hills and curves, I rolled my Volkswagen.

I inherited my golf clubs from an uncle killed in World War II. There were four in the bag as I recall: two putters, a driver, and an iron. My friends and I approached the game as just an enlarged version of miniature golf, really. We just swung harder and were pleasantly surprised to find there were no windmills to take into account on the greens. We played poorly, were uninterested in improvement, and laughed at ourselves and others. Unfortunately, this was to become our overall philosophy of life. We approached everything the same way. When we bowled at the fabulous new automated Arrowhead Lanes, we imitated the mannerisms, nuances, and seriousness of TV bowlers, while depositing balls in the gutters. We filched the green, red, and tan bowling shoes with the sizes displayed on the backs, and wore them to school. The fad never caught on.

I don’t know that we kept score on that golf course. When you start on the second tee, you don’t get a scorecard. Par was probably three for each hole on the course, although I’m sure a good pro could do them all in two, with no hazards, other than the police, who were occasionally summoned when there were, say, fifty golfers on the course and no gate receipts. Our scores were probably in the 60s, respectable on the pro tour, not so hot on a par-3 9-holer.

It was here I developed my pronounced hook shot (something I never could do in bowling) and my noteworthy ability to play amongst tombstones. If your hook was severe, you could hit a drive into the cemetery, where my grandfather was buried. You had to hit for distance, though, to clear the street and the hedgerow. I did that only once, with the assistance of a strong crosswind, and I did have to go look for the ball because I could only afford the one. After paying my respects at the family grave site, I advanced my ball several plots with my iron, before electing to throw the ball back in play rather than trying to chip it over the hedge and the street. It was a decent toss (I played pitcher and third base as a kid), but still short of the green, leaving me two chip shots and four putts before holing out.

A slice on that course could be even worse. The course was positioned—as are so many things in the Midwest—next to pig and cattle pens, and a severely sliced shot could mean wading through animal dung (actual bullshit!) to play your ball. If it were actually in actual bullshit, what to do? Pick it up? With what? Try to hit it out? This may be where the term “chip shot” was coined, I don’t know.

For all the golfers playing the course, not just the ones bad enough to hit into the pens, a southerly breeze through that area turned a round of golf into a memorable odoriferous experience. Ever try to putt and gag at the same time?

The first real golf outing I can remember was with a group of former college buddies a couple of years after we’d all graduated, on a weekend with our wives at a house on Lake Michigan.

Most of them had played golf throughout college. And bridge. I didn’t play golf or bridge because my older brother played bridge and suffered from a dangerously low grade point average as a result. I didn’t want to become hooked on those vices. So I began playing pinball machines on occasion and then for several hours every day. For five years (had the two senior years). We didn’t have carpal tunnel syndrome back then or I would have died from it.

On our outing, we left the house in the morn

ing and didn’t return until early evening, the great length of time owing to the number of strokes I required as well as to the vast amount of time I spent hunting for my ball.

I have tried to block out memories of that golf outing, but I do occasionally have flashbacks. Frankly, I prefer the flashbacks to ‘Nam. I was in a kind of Jerry Lewis mode that day and there were a lot of laughs, all at my expense.

I recall having a golf bag slung over my shoulder, not like you’re supposed to, with the clubs low and by your side, but rather with the clubs riding high behind my right shoulder like soldiers carry rifles. At any rate, when I bent forward to tee up my ball, all of the clubs fell out, cascading over the top of my head. That one had them rolling on the fairways.

I also recall stroking a ball and having a golf cart whir up behind me with a man shouting: “Hey, you just hit my ball!”

“No,” I said, “I think I’ve been playing the Jim Jeffries brand ball all along.”

“I am Jim Jeffries,” he replied. I was unaware golfers sometimes had their names stamped on their balls.

It was on this day, too, that I performed a truly miraculous golf feat that defies both belief and the fundamental laws of physics. Let’s just say if Jesus had done it (at Bethlehem Hills Country Club) they’d be teaching the tale in Sunday School.

I teed up the ball, and of course everyone in my group was staring at me, because they didn’t want to miss something good. What they saw they will likely never see again.

I took a healthy backswing, whipped the driver through, and did manage to strike the ball, rather than pounding the turf behind it or going over the top and completely whiffing as is so often the case. My partners gazed down-range, but could not pick up the flight of the ball. About two seconds after my swing there was a dull thud as it came to earth not more than twenty feet from the tee.

Behind the tee! I had hit my drive backward, apparently stroking it almost straight up but with so much backspin that it landed behind me. This time my friends did not immediately laugh. They were dumbstruck … aghast … awed at that to which they had borne witness.

That was in the early 1970s. Since then I have continued to amuse others by playing my own quixotic brand of golf in which I keep striving to reach the unreachable par. For fifty years I have played pretty much Par Free Golf.

2

Possibly the Last American Male Takes Up Golf

Ten people scurry around the small gym, chasing little plastic balls bouncing off the walls. It sort of resembles handball … a little bit … maybe team handball … played with big teams … and golf clubs … and lots of little hollow balls with holes in them. And mayhem. It closely resembles mayhem.

The little game begins with ten people lined up in the middle, five of them facing one wall and five facing the opposite wall. They stroke the plastic balls at the walls with 9-irons, then scramble all over the place trying to retrieve the rebounds careening this way and that. When the balls ricochet straight back, the players look like hockey goalies trying to make saves.

What is this? This is bizarre, that’s what. This is my golf class. On a Monday night in February, with the temperature 28 degrees outside, here we are trying to learn to play golf inside an elementary school gym in New Jersey.

Can this actually happen?

I’ve signed up for a community school night class, which is not exactly a week at Pebble Beach in the Jack Nicklaus Golf Academy, but it’s a start. And, it’s sixty-nine bucks! For six lessons. And that includes your own personal carpet swatch, which you place on the floor to hit the balls from—although sometimes my particular carpet sample travels farther than the ball.

“Whoa!” exclaims the instructor, Liz Kloak, when the bad golf genie makes my little rug fly. “Watch it there.”

All the students are saying their “I’m sorry”s as they run in front of each other chasing their balls. Or their “Oh! I’m Really Sorry!”s as their mis-struck balls strike fellow students. It could be worse. The balls could be real. Liz says a student in a previous class didn’t quite “get it,” and hit a real ball that came back and struck another student in the foot. Luckily, the victim worked for Johnson & Johnson and had bandages in her car.

Our motley group is clearly not ready for hoity-toity golf schools anyway, and is better off by far in the capable, compassionate hands of Liz, who loves golf as it was gently taught to her by her kindly father. She’s a great golfer, but as a mother of three who’s six months pregnant (“my stomach is costing me fifteen yards on my drive”), she has some perspective, always saying reasonable, comforting words to us like “It’s just a game” and “So, don’t keep score.”

She also has a great Boston—“Bahstan”—accent: “Do it this way and you’ll get mo-ah yahdage and a bettah chance at pah.” Students occasionally ask for a translation.

“Look at the ball!” she bellows, but amiably, at a student whose carpet is scooting across the gym.

“Don’t try to kill it!” she hollers to a guy who has swung as hard as he can and has missed the ball entirely.

“Face the direction you want to hit it,” she admonishes a cockeyed student.

That would seem obvious, but this is your basic instruction. A class for rank beginners. “Say you’re a ‘novice,’ “ Liz suggests. “It sounds better than ‘beginner’ and doesn’t scare the golfers around you as much.”

Students in her two back-to-back evening classes range in age from eleven years old to sixty-seven. Six men and five women in the first seventy-five-minute class, nine women and one man in the second. There are couples taking up golf together, women who want to take it up for business reasons, other women who want to be able to play golf with their husbands because that’s the only way they’ll ever see them, still other women who think they might meet rich men on the golf course, men who are giving up on more strenuous sports, and men and women alike who just think golf looks like fun. “I don’t take it too seriously,” says Michelle, hitting one sideways. “I can be miserable at home.”

We don’t even know how to hold a club, so Liz starts with the grip. Unfortunately, four of us are out of town for that first class. The next week she works on the swing. Unfortunately, the four of us have not been notified that the class has been relocated, so we meet at the wrong location for Class No. 2 and shoot the breeze for twenty minutes before figuring out there’s a problem and heading home. Now, we’ll only have four classes to learn golf.

“I told you we should have taken Tiger Schulmann’s karate class,” one of our estranged foursome says to her friend. These two are taking the class together—to learn golf, yes, but also to get the hell out of the house one night a week. The friend doesn’t seem to mind at all that she’s wasting time at the wrong location missing golf class, “just so I get home after the kids are in bed. Let’s go over to Finnegan’s [bar] for a drink.”

At Class No. 3, Liz gives the four of us a quick course in the grip: “Your left hand is your rudder. Your thumb goes straight down the shaft. Grip it firmly but don’t white-knuckle it. Your right hand can be rotated clockwise or counterclockwise slightly to adjust your shot. Clockwise opens your grip to stop hooking … the opposite to stop slicing.” Got it? Okay.

She speeds ahead. “Now, in your stance your feet are shoulder width wide, your knees are bent, with all joints relaxed. Keep your head down and swing slowly. Get over that kill thing. If you swing hard and fast you don’t hit it squarely. Hitting the sweet spot generates power. That’s why 120-pound women can hit it three-hundred yards. Do not accelerate on the downswing. For more distance just take it back farther. Same tempo up and back. Count 1–2-3 up and 1–2-3 down like a pendulum if you have to.”

Slow down. Bring your left shoulder into your sight plane on the backswing, then bring your right shoulder into your sight plane. My mother wears purple so she sees her shoulders. “And finish. Throw the club over your shoulder—no, gently, or you’ll break your neck—on your follow-through. And when it’s a good shot, stand

there with that club over your shoulder and admire it in a pose for a minute, like this, even if it annoys your partners. My husband always has to tell me ‘that’s enough!’ ”

Okay-okay-okay-I’ve-just-heard-more-about-golf-in-five-minutes-than-I’ve-been-told-in-fifty-years. But how can you possibly remember to do all those good things at once? Yogi Berra said “You can’t think and hit a baseball at the same time,” and for once he made sense.

There’s a lot to learn when you’ve picked up your swing from watching highway maintenance crews cutting weeds along the interstate. This will take time. More than I have left here on the firmament, unfortunately.

The four of us join the group and begin to hit our first balls. “Generate loft!” Liz instructs a student who is on his hands and knees the whole class searching for the balls he’s firing under the pile of tumbling mats in the corner. “Launch, don’t push.”

One student disappears for ten minutes and finally walks out from behind the curtain on the stage, where he’s lost a few balls. I’m thinking that if we’re losing balls in this little gym it does not bode well for us in the great outdoors—which is quite vast.

Indeed, Liz cautions: “If you hook it or slice it here, you’re really going to hook it and slice it on the course.”

Halfway through the seventy-five-minute class, one woman has yet to hit the gym wall, which is a large target just twenty feet away. On that wall hangs a poster of Cal Ripkin staring back at her. Below Cal’s picture in six-inch-high letters is the word “Perseverance.”

“Remember, bad shots tell you more than good shots,” she says encouragingly as I hit a ball sideways. In my case I think they might be telling me to leave.

Fore! Play

Fore! Play